|

35,000 Year Old Stone Age Flutes

Newspaper Articles

|

(This instrument is an end-blown flute with four finger holes and a V-shaped mouthpiece at the top.

It may very well be the oldest-known ancestor of the shakuhachi. -MHL)

STONE AGE FLUTES ARE WINDOW TO EARLY MUSIC

June 25, 2009

By John Noble Wilford

New York Times

At least 35,000 years ago, in the depths of the last ice age, the sound of music filled a cave in what is now southwestern Germany, the same place and time early Homo sapiens were also carving the oldest known examples of figurative art in the world.

Music and sculpture — expressions of artistic creativity, it seems — were emerging in tandem among some of the first modern humans when they first began spreading through Europe or soon after.

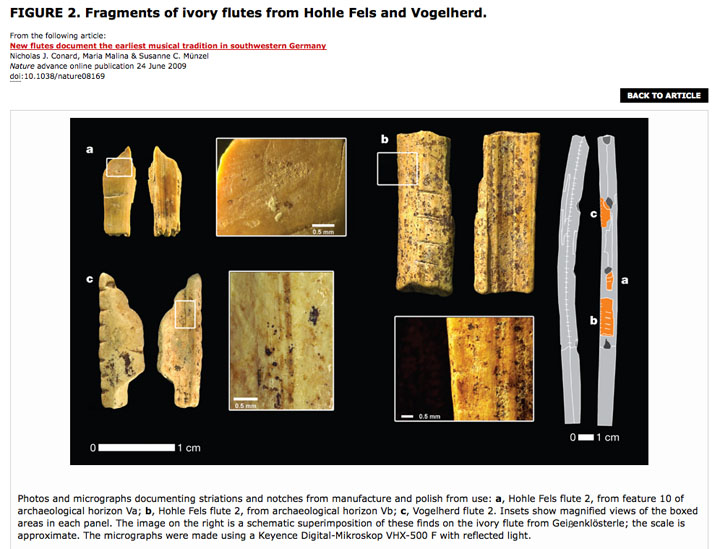

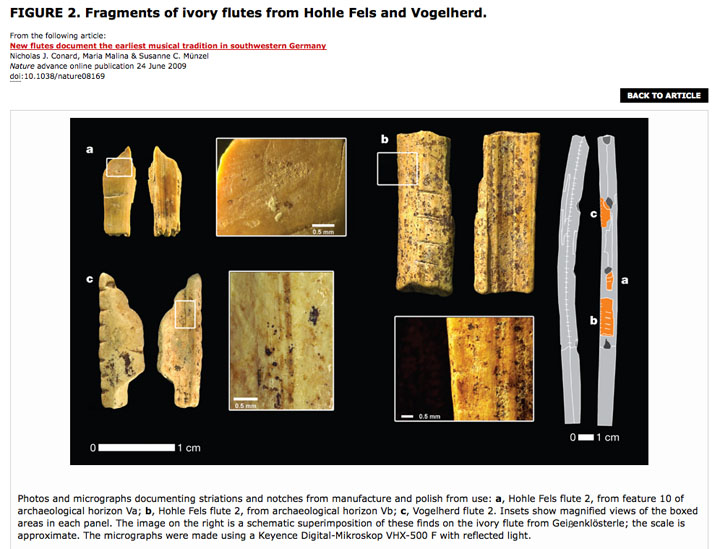

Archaeologists reported Wednesday the discovery last fall of a bone flute and two fragments of ivory flutes that they said represent the earliest known flowering of music-making in Stone Age culture. They said the bone flute with five finger holes, found at Hohle Fels Cave in the hills west of Ulm, was “by far the most complete of the musical instruments so far recovered from the caves” in a region where pieces of other flutes have been turning up in recent years.

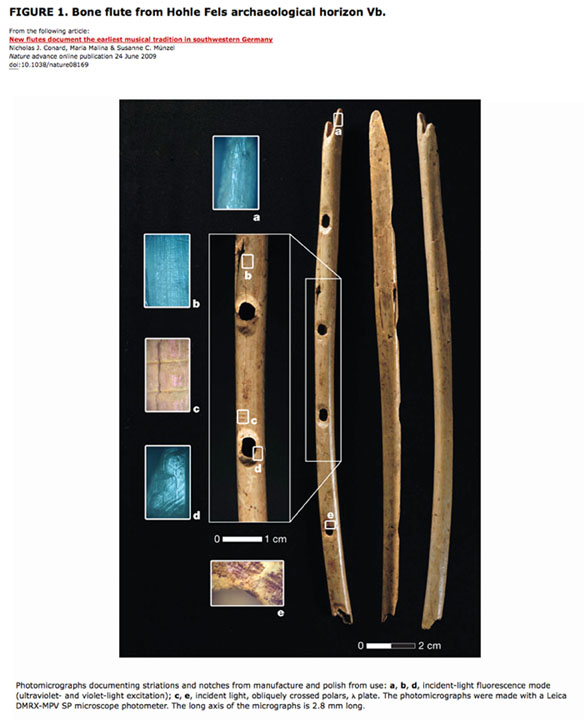

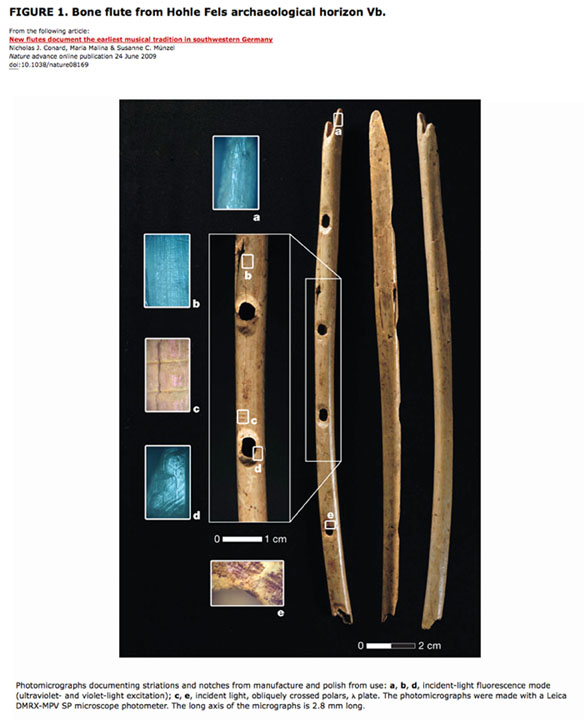

A three-hole flute carved from mammoth ivory was uncovered a few years ago at another cave, as well as two flutes made from wing bones of a mute swan. In the same cave, archaeologists also found beautiful carvings of animals.

But until now the artifacts appeared to be too rare and not as precisely dated to support wider interpretations of the early rise of music. The earliest solid evidence of music instruments had previously come from France and Austria, but dated well after 30,000 years ago.

In an article published online by the journal Nature, Nicholas J. Conard of the University of Tübingen, in Germany, and colleagues wrote, “These finds demonstrate the presence of a well-established musical tradition at the time when modern humans colonized Europe.”

Although radiocarbon dates earlier than 30,000 years ago can be imprecise, samples from the bones and associated material were tested independently by two laboratories, in England and Germany, using different methods. Scientists said the data agreed on ages of at least 35,000 years old.

Dr. Conard’s team said that an abundance of stone and ivory artifacts, flint-knapping debris and bones of hunted animals were found in the sediments with the flutes. Many people appeared to have lived and worked there soon after their arrival in Europe, assumed to be around 40,000 years ago and 10,000 years before the native Neanderthals were to become extinct.

The Neanderthals, close human relatives, apparently left no firm evidence of having been musical.

The most significant of the new artifacts, the archaeologists said, was a flute made from a hollow bone of a griffon vulture, skeletons of which are often found in these caves. The preserved portion is about 8.5 inches long and includes the end of the instrument into which the musician blew. The maker had carved two deep, V-shaped notches there, and four fine lines near the finger holes. The other end appears to be broken off; judging by the typical length of these bird bones, two or three inches are missing.

Dr. Conard’s discovery in 2004 of the seven-inch, three-holed ivory flute at the Geissenklösterle cave, also near Ulm, inspired him to widen his search of caves, saying at the time that southern Germany “may have been one of the places where human culture originated.”

Friedrich Seeberger, a German specialist in ancient music, reproduced the ivory flute in wood. Experimenting with the replica, he found that the ancient flute produced a range of notes comparable in many ways to modern flutes. “The tones are quite harmonic,” he said.

A replica is yet to be made of the recent discovery, but the archaeologists said they expected the five-hole flute with its larger diameter to “provide a comparable, or perhaps greater, range of notes and musical possibilities.”

Archaeologists and other scholars can only speculate as to what moved these early Europeans to make music.

It so happens, as Dr. Conard and his co-authors, Susanne C. Münzel of Tubingen and Maria Malina of the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences, noted, the Hohle Fels flute was uncovered in sediments a few feet away from the carved figurine of a busty, nude woman, also around 35,000 years old. The discovery was announced in May by Dr. Conard.

Was this evidence of happy hours after the hunt? Fertility rites or social bonding? The German archaeologists suggested that music in the Stone Age “could have contributed to the maintenance of larger social networks, and thereby perhaps have helped facilitate the demographic and territorial expansion of modern humans.”

'OLDEST MUSICAL INSTRUMENT' FOUND

June 25. 2009

By Pallab Ghosh

Science Correspondent, BBC News

Scientists in Germany have published details of flutes dating back to the time that modern humans began colonising Europe, 35,000 years ago.

The flutes are the oldest musical instruments found to date.

The researchers say in the Journal Nature that music was widespread in pre-historic times.

Music, they suggest, may have been one of a suite of behaviours displayed by our own species which helped give them an edge over the Neanderthals.

The team from Tubingen University have published details of three flutes found in the Hohle Fels cavern in southwest Germany.

The cavern is already well known as a site for signs of early human efforts; in May, members of the same team unveiled a Hohle Fels find that could be the world's oldest Venus figure.

The most well-preserved of the flutes is made from a vulture's wing bone, measuring 20cm long with five finger holes and two "V"-shaped notches on one end of the instrument into which the researchers assume the player blew.

The archaeologists also found fragments of two other flutes carved from ivory that they believe was taken from the tusks of mammoths.

Creative origins

The find brings the total number of flutes discovered from this era to eight, four made from mammoth ivory and four made from bird bones.

According to Professor Nicholas Conard of Tubingen University, this suggests that the playing of music was common as far back as 40,000 years ago when modern humans spread across Europe.

"It's becoming increasingly clear that music was part of day-to-day life," he said.

"Music was used in many kinds of social contexts: possibly religious, possibly recreational - much like we use music today in many kinds of settings."

“ These flutes provide yet more evidence of the sophistication of the people that lived at that time ” - Professor Chris Stringer Natural History Museum

The researchers also suggest that not only was music widespread much earlier than previously thought, but so was humanity's creative spirit.

"The modern humans that came into our area already had a whole range of symbolic artifacts, figurative art, depictions of mythological creatures, many kinds of personal ornaments and also a well-developed musical tradition," Professor Conard explained.

The team argues that the emergence of art and culture so early might explain why early modern humans survived and Neanderthals, with whom they co-existed at the time, became extinct.

"Music could have contributed to the maintenance of larger social networks, and thereby perhaps have helped facilitate the demographic and territorial expansion of modern humans relative to a culturally more conservative and demographically more isolated Neanderthal populations," they wrote.

That is a view supported by Professor Chris Stringer, a human origins researcher at the Natural History Museum in London.

"These flutes provide yet more evidence of the sophistication of the people that lived at that time and the probable behavioural and cognitive gulf between them and Neanderthals," he said.

"I think the occurrence of these flutes and animal and human figurines about 40,000 years ago implies that the traditions that produced them must go back even further in the evolutionary history of modern humans - perhaps even into Africa more than 50,000 years ago.

"But that evidence has still to be discovered.

Atricles - Table

of Contents

Atricles - Table

of Contents

Tai Hei Shakuhachi Homepage

Tai Hei Shakuhachi Homepage

Main Menu

Main Menu