MONTY LEVENSON: The music I play is

called Honkyoku. That means "original music." It is

the music that comes out of the Fuke legend and the Kinko tradition.

When I blow shakuhachi, I blow with ritual and with posture. And

I bow because it puts me in the proper relationship to that tradition

and the spirit of that music.

There is something more than tradition, culture

and rituals passed down over a long period of time that is going

to help us out in the end. My particular interest is in the stuff

that underlies or cuts through culture, that connects us all as

a species, as human beings.

There is something more than tradition, culture

and rituals passed down over a long period of time that is going

to help us out in the end. My particular interest is in the stuff

that underlies or cuts through culture, that connects us all as

a species, as human beings.

Many of my feelings come from my experience

with my family, especially my father who had a hard life and experienced

much suffering. He was sick for ten years and died at the age

of 56. Most of his life consisted of hard work and frustration.

Toward the end of his life, the last couple of years, he was confined

to a bed at home. The tradition he was raised in was very strong

around him. We grew up in an conservative Jewish community and

were surrounded by Chasidim, a sect of ultra-orthodox Jews. In

the end this tradition was useless to my father. It became mere

ritual whose deeper meaning and personal relevance had dissipated.

What was left of his religion was closer to superstition.

He had a hard time with that loss. I

was part of the process of his illness and death and saw very

clearly what a void he experienced and how much that affected

him. Here was a man, steeped in tradition and the enduring culture

of Judaism, who at the end could only deny God and flail out at

his circumstance.

There has got to be more to it than

those postures that are passed down over time. If they are empty

of information they are not going to suffice. If there is no direct

correlation to one's personal experience they become a source

of torment rather than compassion and help.

You asked me why I blow shakuhachi.

I blow shakuhachi instead of flailing. I blow shakuhachi to experience

the center. To be close to that place means being close to the

meaning. Our own culture here in Mendocino County, California

has to do with evolving rituals and traditions that are emerging

from real conditions and experience in this place.

I have never been to Japan. My involvement

with shakuhachi has occurred without ever having left my home

in Willits. It gives me a unique perspective. I am very involved

with this tradition, but I come from outside of it completely.

All of my work has been done right here on this coastal mountain

ridgetop.

HOW DOES THE SHAKUHACHI DIFFER FROM

OTHER ANCIENT WIND INSTRUMENTS?

Shakuhachi is a piece of bamboo with

five holes in it. The end of the instrument is cut off at an angle

which one blows across to produce a sound. Facts about shakuhachi

are mixed with legend; nobody knows where one begins and the other

leaves off. I believe what is historically filtered down to us

through time - whether true or not - is relevant.

Some ethnomusicologists believe that

an instrument of this type dates back to ancient Egypt. The shakuhachi

was we know it, however, came to Japan from China. The legend

that is most popular is that of Fuke, a Chinese zen monk who lived

in the 10th century during the time of the T'ang Dynasty. Fuke

ran around with a bell he would ring to the accompaniment of a

poem. The essence of the poem he recited was that if you encounter

somebody who is very bright, smack him on the head. If you encounter

somebody who is dull, smack him on the head. In fact, if you encounter

anything at all, smack it on the head. And if you encounter emptiness,

in particular, be sure to smack it on the head severely!

Fuke was an eccentric to say the least.

He was a madman who played a flute, rang a bell and smacked people

on the head. Naturally he had a large following.

The shakuhachi came to Japan in the

13th century, brought from China by a monk named Kakushin. But

it was much later, during the Tokugawa era of the 17th and 18th

centuries when feudal Japan was coming to an end, that the instrument

evolved to its present form. As Japan was becoming centralized

under a single administrative authority represented by the Shogun,

the influence of the once powerful feudal lords was diminished.

These daimyo had a very wide following of samurai who were suddenly

set free from allegiance to their masters. This change had a tremendous

impact on Japanese society. Generations of the same class structure,

lifestyle and mode of livelihood - very deep connections - were

severely and rapidly disrupted.

Some of these masterless samurai or

ronin became what was known as Komuso. They were not quite monks.

The komuso were more like pilgrims who wandered through the countryside

often involved in the politics and intrigue of the time. This

sect of masterless samurai took to blowing shakuhachi and later

received the exclusive privilege of using this instrument to solicit

alms.

At one point the ronin were forbidden

to carry their revered samurai swords. That was one way in which

the shogun was able to control a dangerous and potentially threatening

class of warriors. Here we return to legend which has it that

some of these komuso redesigned the shakuhachi - originally made

from a flimsy piece of bamboo - and fashioned it from the root

of the bamboo which is a very substantial, thick and heavy part

of the plant. In this way the shakuhachi doubled in its use as

weapon.

In the hands of the komuso the music

of the shakuhachi also blossomed and took a form that survived.

This flowering was formalized by a man named Kurosawa Kinko who

lived during the 1700's. Kinko traveled all over Japan collecting

music which he put together in a repertoire of 36 pieces. This

became the first written or notated music for shakuhachi. The

piece I played for you - Cho Shi - is the first piece of the Kinko

repertoire. The music is still being taught and learned in the

form preserved by Kurosawa Kinko.

IT SOUNDS MORE THE MUSIC OF A HILLSIDE

THAN A CHAMBER. THE CLOSER YOU GET TO THE INSTRUMENT, THE MORE

YOU ARE AWARE OF THE BLOWING, THE SOUND OF THE INSTRUMENT THAT

IS NOT THE SOUND OF THE MUSIC.

Many people do not regard the sound

of the shakuhachi as music at all. Shakuhachi is different and

this difference is one of emphasis which has to do with the context

of sound. If you think of music as having a beginning, a middle

and an end, a context is established through which the sound moves

and develops. In blowing shakuhachi the emphasis is on each individual

note and the relationship between the notes. The music has a definite

quality of randomness or vagueness.

I played shakuhachi for ten years before

I began to study the traditional music. In studying this music

it became clear to me that each note and progression of notes

becomes a focal point in the blowing. The pauses, little grace

notes, and even the spaces between the notes, are elemental in

this musical form. A traditional shakuhachi piece can never be

played the same way twice. While all aspects of the notation governing

pitch, meter and intonation are clearly - often strictly - presented,

the way in which the sound is produced and the manner in which

the flute is blown is entirely up to the player at the time he

is blowing. This built-in "improvisational" aspect of

presentation is intentional and relates to the religious origins

of the shakuhachi. Fumio Koizumi is quoted as saying that "the

sound of the bamboo flute leads the mind directly into spiritual

thought. A single note of the shakuhachi can sometimes bring one

to the world of Nirvana."

Religious is not quite the right word

to describe my own blowing. Koizumi's quote reads to me like an

admonition. My efforts may be more directed if somewhat less exalted.

It has to do with practice and the focus on movement from one

point to another. Of late this practice has required me to put

the shakuhachi completely away and listen rather than blow. Like

the music that can end suddenly, there is no wind up, no apparent

conclusion. Simply a movement between sound and silence.

MUCH WESTERN MUSIC IS MADE TO BE HEARD.

THIS MUSIC IS MORE MADE TO BE PLAYED.

Exactly. Shakuhachi is made to be blown.

There is no shakuhachi without breath. My interest in blowing

comes from my interest in trying to be aware of what is happening

when it's happening. It's that simple. The extent that I put energy

into shakuhachi is the extent to which I put energy into trying

to be awake.

Looking at myself honestly I have to

say that most of the time I am not very awake. [laughs] So I find

it really helps to practice. Of course, shakuhachi is very much

involved with breathing. It is a direct reflection of breath.

The sound comes out and goes back in, following breath, and there

is important information being conveyed in that process as in

some form of biofeedback. For me, that information has become

relevant. More so than watching the 11 O'clock News.

WHAT HAS BECOME OF YOU, MONTY? YOU AS

CHARACTERISTIC OF A BEVY WITHIN A GENERATION? YOU'VE TAKEN YOUR

WESTERN FRAME AND ARE WRAPPING IT AROUND EASTERN RITUALS, DAY

AFTER DAY, MONTH AFTER MONTH, AND NOW AN ADULT LIFETIME. . . WHAT

KIND OF AMALGAM ENSUES? HOW HAS THIS POSTURE AND THE MUSIC THAT

PREOCCUPIES YOU ALTERED YOU, A WESTERN MAN?

I am still very much a western man. But more

than assuming any given posture or presenting certain characterizations,

my interest is in learning. If you keep at something long enough,

you come to the limit of certain parameters. At that juncture

you can either stay where you are or open yourself up to other

forms and processes.

I am still very much a western man. But more

than assuming any given posture or presenting certain characterizations,

my interest is in learning. If you keep at something long enough,

you come to the limit of certain parameters. At that juncture

you can either stay where you are or open yourself up to other

forms and processes.

I can think of myself sitting here blowing

shakuhachi and perhaps there is someone in Kyoto doing the same

thing. We are assuming the same posture, but it hardly matters.

That posture is no more than a form to still the body, quiet the

mind and focus one's attention on breath. It doesn't matter which

way you come to it, east or west.

The fact that this person is Japanese

and lives in Kyoto while I am an American in the hills outside

of Willits is something we can drop away for a moment. Let's forget

about where we've come from or where we've been and look at where

we are at that moment. Observing things from this perspective

may provide us with some useful and very practical information.

In seeing our shared relation to the whole we remain unique and

distinctive without necessarily being adversarial. Acting on this

perception is the first step toward peace.

My involvement with shakuhachi is not

motivated by any desire to attach myself to something alien or

esoteric. It is more a means to learn who I, in fact, am. And

it comes out of a process which is occurring right here in these

hills. Call it what you will.

TWENTY YEARS OF HILLSIDE CULTURE HAS

EMERGED HERE. NOT TOTALLY AN INTENTIONAL INVENTION. MUCH OF IT

IS THE RESULT OF LIVING ON A SLOPE WITHOUT CITY WATER, DETACHED

FROM CENTRALIZED POWER.

I have been living on this hill for

sixteen years, in Willits since 1970. My coming here started out

as one thing and quickly emerged into something else. My experience

is similar to that of many others who moved here during that period.

You buy a piece of undeveloped land

with nothing on it in the way of amenities. You haul water, use

candles and kerosene lamps for light and eventually build a house.

I lived in a little shack for a year that was red-tagged by the

government a week after I moved in. I moved on the land in October,

at the beginning of the rainy season. Friends advised me to wait

until Spring, but there was no way that I was going to wait. The

large enclosed garden down by the entrance to the place was built

between storms. You go right to work, attempting to take care

of the basics: keeping yourself warm and fed while trying to get

running water into the house.

After a couple of years of hiking around

the land I finally began to realize something about the place

I was inhabiting and its relationship to the larger ecosystem.

I began noticing the tree stumps. Taking you on a tour of these

80 acres I could show you no less than a hundred Douglas fir stumps

that are four to five feet in diameter. That took years for me

to see. This forest was very different 40-50 years ago prior to

the time it was logged. A neighbor living down the road did most

of the cutting. He lived here for thirty years and was related

by marriage to the original white settlers of String Creek valley.

He and I overlapped one year. I moved here just as he moved to

town.

That really impressed me. When I started

out, I was thinking that this way my land. Having grown up in

Brooklyn, I never owned anything. My family worked and struggled

all their lives and had nothing to show for it but debts. They

never owned much. We lived in a slum neighborhood with a lot of

other people who even worse off than ourselves. Everybody was

struggling, trying to do the best they could. I never lived in

a house until I moved to Willits. Never had a yard with trees

or space around it. I never owned a car.

The way things went for me was that

suddenly I owned a large area of land in these beautiful coastal

foothills on which I was going to make a place to live. My understanding

of that process was about to be radically changed in a few short

years. I realized that the land I was homesteading had been utterly

devastated. "Rape" is a better word to describe what

had occurred here. This must have been a magnificent spot. A thriving

forest of century-old virgin firs. My house is built on top of

what used to be a logging platform. This big flat area was created

years ago as part of the timber harvest operation. All of the

top soil was removed. You can still find slash everywhere. My

driveway is an old skid road. I can show you giant fir trees -

five feet in diameter - that were cut and left to rot on the ground.

When I realized what had happened here,

it changed my attitude significantly. The process of living here

ceased to be strictly a matter fulfilling my dreams - building

a house, raising a family. It suddenly became a grave responsibility.

RESPONSIBILITY TO DO WHAT?

I can draw a circle around myself as

I can draw one around my family and the other people with whom

I now share this land. I can draw a circle around these 80 acres,

around my neighbors on String Creek, around Willits and Mendocino

County. Within the perimeter of these concentric circles I have

certain kinds of responsibility. Now I also have responsibilities

outside of these circles as well which I have come to see as increasingly

global and cosmic. But basically within the boundary of my land,

whatever is going on is my business. I've decided what is going

to occur here will be activities and projects that are sustaining.

Energy that is going to be good and right, not bad. And I am the

person to decide what is good and what is right.

For one thing, there is not going to

be a lot of big trees cut down. Which is not to say that I haven't

cut down some trees. But anything I do cut down will be part of

a greater consideration of value. I am going to be thinking about

the big picture which is important in doing things responsibly.

THE BIG QUESTION IN THIS REGION IS HOW

DO YOU PUT TOGETHER A LIVELIHOOD THAT WORKS. YOU'VE PIECED TOGETHER

A WORLD-WIDE MARKET TO A MICRO-REGIONAL ONE. WAS THAT INTENTIONAL?

HOW DID IT END UP BEING SIGNS AND FLUTES?

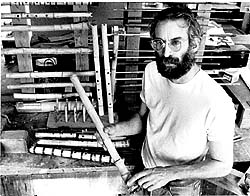

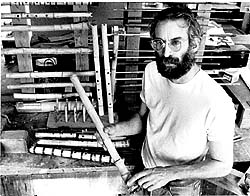

I had a sign business in this town for

sixteen years before going back to making flutes full time. That

certainly was not intentional. I am one of those non-serious artist

types. It's something I've always done as a gig. "Art-for-money."

When I was in college I worked my way through school as a commercial

artist in New York. At the university, I studied sociology. I

was the only Marxist in the advertising agency.

While back east, I attended graduate

school at the New School for Social Research and then at Brandeis

University. I was very much involved in the student and anti-war

movements and in the civil rights movement since the early days

- '63 on. My last year at the university was largely taken up

by a nationwide student strike against the war in Vietnam. It

was during that time that students at Kent State University in

Ohio were killed by the National Guard. I was on the steering

committee for that strike which was centered at Brandeis. I was

quite a year. Many realizations occurred to me about the world

into which I was about to make my way.

In 1970 I was offered a teaching job

at California Institute of the Arts which hadn't opened yet. It

was the first year of the school's existence. A professor I worked

with at Brandeis was hired to set up what he called the School

of Critical Studies. He in turn hired several east-coast radicals

including Herbert Marcuse, a German social theorist regarded during

the 60's as "the Father of the New Left." Marcuse's

work was seminal to my own research, so the job offer was a unique

opportunity. Cal Arts, however, was funded with money donated

by the Disney family which was influential in right-wing California

politics at the time. When they discovered what was developing

at the school, they fired everyone. Marcuse was fired before he

ever got there.

These events changed my mind about moving

to Los Angeles. I had friends in Berkeley who had moved up north

to a small town called Willits. These friends found a place in the

country with a house nearby that I was able to rent for $40 a

month. I was living in Boston at the time, never seriously intending

to move to northern California or live in this cabin on a permanent

basis. When things fell through at Cal Arts it was clear that

what I really needed to do was get away from the University for

awhile and finish writing my doctoral thesis. I had a grant from

the National Science Foundation which was paying me to write Marxism.

So I headed out west to Willits with 500 books and the idea of

spending part of a year secluded in the woods to write. That was

20 years ago and I'm still here.

It took two month for me to realize

that a phase of my life had ended. It came as a total surprise.

I remember sitting on the front porch of the cabin realizing that

I was never going to finish this thing. I was never going back

to the University. I was completely done with the whole process.

I had no idea what lay ahead. It felt good to be where I was at.

I was then that I encountered shakuhachi.

Almost the same week.

Much of what we did in Willits during

the early days was to play music. We acquired some instruments

from a West German flutemaker who passed through the area and

began to blow shakuhachi. These instruments were very limited.

I began to work on shakuhachi with the hope of making a decent

instrument to play. I'm still trying.

I WANT YOU TO TALK ABOUT YOUR INNOVATIONS.

WHAT ARE THE DETAILS AND DECISIONS YOU'VE MADE IN THE PROCESS

OF ADDING TO AN INSTRUMENT THAT IS 4000 YEARS OLD?

Let me go back to Berkeley in the early

'70s. There was no money and the rent was coming up. I drove down

to Berkeley with several flutes and set up on the sidewalk in

front of Cody's Bookstore on Telegraph Avenue. I made $80 that

weekend which was very inspiring.

I returned to Willits and set up a workshop

in my bedroom. Every few months I'd drive down to the City or

attend a local craft fair and usually come home with enough money

to pay the rent.

Then I was visited by Dick Mendes, a

former professor of mine from Brooklyn College, who turned me

on the Whole Earth Catalog. He suggested that I go see these people,

which I did. I walked into the Whole Earth Truck Store with several

flutes and there was

Brand. Stewart eyed me and said:

"Ah, Shakuhachi!" He took one of my flutes and wandered

off into a corner. I could hear him huffing and puffing for over

half an hour. I was impressed that he not only knew about shakuhachi,

but could get a sound out of one immediately. It took me four

days to accomplish that feat. Stewart returned and said that he liked the flutes, suggesting that I write a letter to the Catalog

immediately as it was going to be printed the following week.

So I did. About two months later I had so much response I was

back ordered for three months. That went on for six years. I was

barely able to keep up with it all.

TELL ME ABOUT YOUR FLUTE - HOW IT DIFFERS,

HOW YOU HAVE TRANSFORMED THE STRUCTURE.

During those six years I spent quite

a bit of time working with bamboo. There were no books in English.

There was nobody around to draw from. I was left to my own devices

in an attempt to improve the quality of the instrument. In retrospect,

those years where very important to my understanding of what shakuhachi

is all about.

My feeling at the time was that I would

never be able to make a good instrument. So I never got caught

up in aspirations of "mastery." That seemed like a such

a remote possibility, it didn't concern or hinder me. Nor did

it stop me because it soon became clear that there was a genuine

need for shakuhachi in our emerging counterculture. Where that

need arose from, I am not sure. Many people were captured by the

sound of this simple bamboo flute.

I spent a good deal of time making mediocre

flutes. They were out of tune and funky. But they blew the basic

stuff and everyone I met loved them. That kept me going. I didn't

have much of a notion to make "great" instruments. I

didn't know much about what I was doing.

I spent a good deal of time making mediocre

flutes. They were out of tune and funky. But they blew the basic

stuff and everyone I met loved them. That kept me going. I didn't

have much of a notion to make "great" instruments. I

didn't know much about what I was doing.

Ten years down the road that became

a problem. I had reached a natural limit in what I was able to

accomplish by myself. I had improved all aspects of the flute

except its most critical one: the basic design of the bore. I

began to think that it was time to quit or find some help - which

meant going to Japan. Finally, things came to a crisis. I was

either going to make shakuhachi or to stay on the land. I couldn't

see myself doing both.

I had met an American - Tom Deaver -

who had gone to Japan in the early 70s and did a traditional apprenticeship

in shakuhachi. Tom has been very helpful and encouraging to me

over the years. At that time he suggested that I come to Japan

to learn shakuhachi. My coming, he felt, was the only way I was

going to do it. I recall feeling that he was correct - that I

needed to make a commitment. Soon, however, it became apparent

that what I want to do most was to stay on the land. There was

no real choice as my work here was far more important. So I did

not go to Japan, but kept at making my primitive shakuhachi. I

never really stopped.

HOW DID YOU CHANGE THE FLUTE?

Well, here I am ten, twelve years into

this process and I am still turning out junk. But everyone loves

these simple flutes. A couple of people I made shakuhachi for

went on to Japan to study with great masters. And then there are

all these folks getting off blowing. That kept me at it.

Doing mostly mail order, I put together

a small catalog which eventually became the primary source of

access to information on the shakuhachi. The catalog is now 75

pages and is distributed all over the world. A lot of people got

turned on to shakuhachi through this catalog. That in itself made

my efforts worthwhile, but I still was not making what I considered

to be decent flutes. By decent, I mean a flute that someone would

be able to use in studying the traditional music. My flutes were

simply not good enough for that.

WHAT WAS LACKING?

Precision in the bore. I wasn't making

- or unmaking - the inside of the bamboo precisely enough. And

after a number of years, I decided that I should either go to

Japan or give it up. However, it could not leave Willits for one

reason or another. For three more years I put aside all efforts

at trying to improve the bore of my instruments. I had been experimenting

with different techniques of fabrication which I abandoned assuming

that what I needed to do most was get to Japan. There seemed no

point in thinking about improving my shakuhachi until I did so.

When it appeared that I was going to

make it abroad - that it was finally going to happen - I had the

door slammed in my face. [laughs]. But that is a classic story

in Japan. The deshi comes to the door and the master slams it

in his face saying: "Go back home. Come back next year."

That happened to me in a manner of speaking.

And I am utterly grateful for it, because

when I realized that I was not going to Japan, I also realized

that I did not have to go. I did not, in fact, have to do anything

different from what I had been doing all these years here on String

Creek in Willits. I went back into the workshop with a very different

sense about what I had to do. Within one month I figured out how

to make precision bores.

By "precision bores," I mean

a bore that is controlled in its diameter to within a few hundredths

of a millimeters along the entire length of the flute. The technique

I have developed enables me to measure and duplicate the bore

of a very fine instrument with extreme accuracy. By casting the

interior I am able to make a quality shakuhachi in a fraction

of the time and for a fraction of the cost of a traditional instrument.

WHAT IS THE SPECIAL CHALLENGE OF THE

FIBER INVOLVED - THE BAMBOO?

To begin with, you cannot find it here

at all and it is very difficult to obtain even in Japan. Shakuhachi

is made from the root of the bamboo. The culm has to be dug up,

cleaned and cured. The entire process is labor intensive. The

node placement of the fushi along the length of the plant is very

critical as is the shape and external diameter of the bamboo.

It is not uncommon for a maker in Japan to purchase a piece of

green bamboo for as much as $100.

Shakuhachi are very expensive in Japan.

The maker who buys his raw bamboo for $100 sells his finished

instruments for as much as two to three thousand dollars. The

craft is pretty much ensconced in a guild system. Everybody has

secrets. Cooperation extends to keeping the prices of instruments

high. If you want to study shakuhachi, you had better be, at least,

middle class. Because $400 is required for an adequate practice-grade

flute. After a year of study, most people make an investment of

about $1500 for an upgraded instrument. If you are serious, you

need more than one. There are about different twelve sizes of

shakuhachi made. That can get very expensive.

My sense is that shakuhachi is not easily

accessible to many people here or in Japan. Part of my commitment

is to make flutes that are both high quality and affordable. Most

important is the need for people to satisfy a primitive urge to

blow, simply blow, shakuhachi. Hopefully my efforts will contribute

toward that end.

WHAT IS THIS URGE TO BLOW?

Let me get to that... Since shakuhachi

is very expensive in Japan, what I would like to do is establish

a middle ground. I want to make really good instruments that are

not terribly expensive. I want to make flutes for people, not

only professionals.

In Japan, the traditional maker hollows

out a piece of bamboo which he lines with tonoko or powdered stone.

When the inlaid material hardens it is shaped and carefully measured.

Shakuhachi craftsmen are dealing with machinist's tolerances as

they fabricate the space around which the flute exists. They are

making an empty space to exacting specifications. It is a very

difficult process. At a certain point, the surface of the bore

is lacquered with urushi, a lacquer made from a plant that is

akin to poison oak. It is not uncommon for people who begin playing

a new instrument to break out in a severe rash when the lacquer

is still volatile.

In fine tuning the shakuhachi, the maker

blows the flute to determine pitch and evaluate the overall balance

of the instrument. Some notes may be weaker than others. Some

may flutter or break off with a certain intensity of breath. Corrections

can be made by inserting into the flute a wet piece of newspaper

that has been folded into a square. By reducing the diameter at

various places along the length of the instrument, evaluations

can be made in determining the final bore configuration. This

balancing act can go on indefinitely as many variables interact

to affect the overall sound of the shakuhachi.

At some point the maker is satisfied

that he has done all he can to improve the instrument. He puts

a price on the flute, which is usually high because a good deal

of time and energy has been expended in its construction. That

is how these flutes are made in Japan. What I am doing is achieving

a similar result using non-traditional materials in a fraction

of the time involved.

WHAT ARE THESE NON-TRADITIONAL MATERIALS?

Plastic! I cast the bore with epoxy

resin. Actually, I am making what I call a mandrel first. It is

a long, steel column that is turned on a metal lathe to very exacting

proportions. I've learned how to measure the inside of a flute

very accurately and transfer those calculations to a graph. The

graph is then used to determine the profile of the mandrel as

it is being turned on the lathe - a long, male image of the inside

of the flute. This completed form is placed inside the bamboo

as a mold for casting. When the mandrel is removed what is left

is a very clean interior surface that resembles the original flute

I measured. I then begin adjusting the sound for pitch and intonation

by adding or removing material along the bore and around the holes.

This process significantly reduces the

time and cost of material in constructing a shakuhachi. In this

way I am able to make quality instruments out of what one person

described as bamboo "broomhandles." I take that as a

compliment as I am able to make shakuhachi for under $200 - under

$100 - that may not look as nice but play as well as instruments

that sell for seven or eight times the price.

I never made it to Japan, but word of

my flutes is circulating there. Just the other day I was visited

by John Kaizan Neptune, an American who went to Japan in the early

70s. John is an accomplished musician who studied the traditional

music, composes and plays jazz on the shakuhachi. He has also

done an exhaustive study of the physical acoustics of the shakuhachi

bore. There are very few people in Japan who both make and play

shakuhachi with as much proficiency as John. It is not uncommon

for people to purchase high quality

instruments which they bring to him

to have fine tuned.

I had sent John some of my flutes and

he was very impressed in the precision casting technique. He came

to my place to check out the procedure firsthand and liked what

I was doing very much. We are now working together and selling

my instruments to teachers and players in both the USA and Japan.

THE URGE TO BLOW - WHAT IS IT? ANOTHER

SACRED URGE?

I don't think of it as any great mystery,

but I can only speak for myself. It seems like one has to cultivate

an awareness of their immediate surroundings. I feel as if I want

to develop the capacity to experience my life as it is unfolding.

Meditation is nothing more than that. It is literally a "practice."

When I arise from that "alien posture" you talk about,

the life I step into, the life I am about to lead is what counts.

I am trying to develop skills that are relevant within the context

of those concentric circles I referred to earlier. Evolving and

sharpening these skills underlies my own urge to blow. I would

like to be better at what I do and feel that I am making the correct

decisions.

Which gets us back to making shakuhachi.

Coming at it the way I did - from outside of the tradition, never

having left this place - I didn't always know what I was doing.

It was a constant round of mistakes. These mistakes are my teacher.

No books, no sensei. Having come through to this point, I have

a profound faith in the process. Coming at it from zero knowledge.

Really one goes around the zero, not one, two, three, twenty,

one hundred. Staying right at the "not sure" place gets

one to the attitude of: "I don't really know all about this,

but I'm going to give it a try." And suddenly it happens.

Learning.

From Suzuki Roshi little book on zazen

comes the saying "joshaku shushaku:" mistake upon mistake

compounded upon itself. It is a compounding of all your mistakes

that is the sum total what you know. You never leave the zero.

You never leave the whole. With shakuhachi it is the empty space.

Nothing else.

I am really lucky that I am here on

my land because there is really no other place for me to be. This

is my zero place. And suddenly John Neptune as well as other teachers

and players who are very involved with shakuhachi come by to visit

and tell me I have something that people in Japan can appreciate

and benefit from. What they are talking about is the same zero

in the form of a shakuhachi that evolved right out of the hill

culture of Mendocino County, California.

YOU NEVER GOT TO JAPAN, BUT YOU BRING

INTO YOUR LIFE A WOMAN WHO WAS BORN THERE AND YOU MAKE A FAMILY

BALANCED BY HER INFLUENCE. I'D LIKE TO HEAR ABOUT YOUR MARRIAGE.

Let me talk about plastic first...[laughter].

I was making shakuhachi for a few years when I was visited by

a fellow called "Shakuhachi Steve" Mindell. He was one

of the first Americans to emigrate to Japan and become involved

in blowing shakuhachi. Steve lived in Kyoto and studied with the

late Kikusui Kofu. Kofu was one of the most highly regarded teachers

of the traditional music in Japan. When Steve informed his sensei

that he was going to visit the shakuhachi maker in America, Kofu

sent along with him a gift for me. It was a shakuhachi made out

of PVC plastic pipe inscribed with character Mu and Kofu's signature.

I was totally overwhelmed with this present, not knowing what

to make of it. Then Steve told me about his teacher. Kofu lived

in a little room behind a zen temple. Strapped to the ceiling

were numerous lengths of PVC pipe. The whole place was littered

with the stuff. This man was a national treasure and spent most

of his time making flutes out of plastic water pipe for his students

to blow.

Ten years later I was given a record

album of Kofu's. It contained the first piece of shakuhachi music

I had ever heard. Music that stimulated and inspired me to make

these instruments. On the back cover of this album was a photograph

of the flutes Kofu played. Two of the three pictured were made

of plastic. The first shakuhachi music I had ever heard - it turns

out - was played on a plastic flute!

Have you ever read The Forest People,

Colin Turnbull's study of the pygmies of the Ituri forest in Africa?

Many of the pygmy's sacred rituals revolve around a long, bamboo

trumpet called the molimo. During these rites which often go on

for days and sleepless nights, the molimo can be heard in the

depths of the jungle imitating the voices of wild animals. As

the ceremony comes to a climax the sound of the molimo approaches

the center of the village and eventually bursts in upon the circle

of chanting men, knocking them over, scattering the fire they

sit around before returning to the jungle. Only initiated members

of the tribe can see the molimo. For women, children and outsiders,

it is taboo.

After a number of years living with

the pygmies, Turnbull was invited to view the molimo. He was taken

on an arduous hike through the jungle and is barely to keep up

with his two young guides as they run swiftly through the undergrowth.

The journey terminates at a stream where the molimo is traditionally

stored for safekeeping. Removed from the flowing water is none

other than two sections of iron sewer pipe that the pygmies had

ripped off from the European sector of the community. Turnbull

is shocked and appalled.

Laughing at his reaction, the two pygmies

tell him that the molimo used to be made of bamboo, but that it

was too much of a hassle as the instrument would crack all the

time. It was constantly being repaired and replaced. When the

Europeans showed up, they discovered modern sewer pipe which represented

a vast improvement. It was a bit heavy, but it didn't crack and

lasted forever. But most important, the sound was right and it

is the sound that counts.

This story illustrates an attitude that

I've encountered with shakuhachi. There are many people concerned

with shakuhachi who care primarily about the sound which the instrument

produces. It does not matter what the flute looks like, what it

is made of, who made it or where it was made. The right sound

is all that is important.

THE CRUX OF THE GAIAN ETHIC IS THAT

YOU HAVE TO CARE WHAT OBJECTS ARE MADE OF - WHAT COMES DOWN TO

BUILD SOMETHING NEW. TO WHAT EXTENT THE EARTH CAN ACCOMMODATE

ANY PRODUCT AS REFUSE. TO HOLD SACRED ONLY ONE ASPECT OF ANYTHING

IS TO INVITE RUINATION. THE CULTURE THAT IS EMERGING HERE HAS

REVERENCE FOR OLD MATERIALS AND THINGS THAT ARE NATURAL, BECAUSE

THERE IS A HISTORY OF THEM NOT HURTING. THERE ARE CERTAIN RESOURCES

THAT IF YOU DON'T LIVE IN A PLACE WHERE THEY OCCUR NATURALLY,

YOU SHOULD NOT HAVE ACCESS TO. PERHAPS THERE WAS A TIME WHEN WE

COULD LEAD LIVES WITH AESTHETIC VALUES BEING PRIMARY. THOSE TIMES

ARE NO LONGER. YOU CAN'T JUST USE SOUND AS A CRITERIA.

To my way of thinking, with shakuhachi,

the value of the sound is not so much an aesthetic value. The

value of the sound is in the information it conveys.

In Japan, the shakuhachi is made from

only one species of bamboo - madaké, a giant timber bamboo

- that is selected with very stringent criteria for suitability.

One of the problems with Japanese flutes that are imported to

the United States is that they tend to crack. "Explode"

is a better description of what often occurs. Japan is an island,

hence very humid. When these instruments arrive here they experience

a tremendous inversion. The inside and outside of the bamboo expand

at different ratios. The powdered stone used to fabricate the

bore has very little bonding capacity as well as its own coefficient

of expansion. These flutes usually split right through to the

bore rendering the instrument unplayable. That's a serious problem

and one of the reason why you seldom find shakuhachi in American

music stores. It is too risky to import and too much of an investment

to take the chance losing.

My new technique virtually eliminates

the possibility of the instrument self-destructing. While the

bamboo may crack, I guarantee all of my flutes, for the life of

the instrument, from ever cracking through the bore. Epoxy has

tremendous bonding properties as well as a superior resonance.

And it is very compatible with the bamboo.

I WOULD LIKE YOU TO TALK ABOUT YOUR

FAMILY NOW.

You want to hear the whole story? I

was all set, finally, to go to Japan, being deep into my midlife

crisis. I was ready to get out of here for awhile. My mother tells

me that I took my first step at six months old and by nine months

I was walking the way I do now. I like to tell people that I didn't

start crawling until I was 37. I was ready for a change.

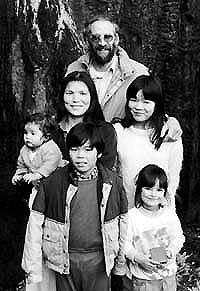

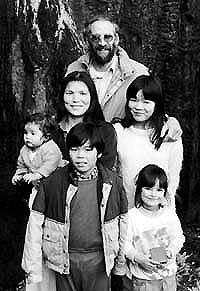

My wife, Kayo, had been in this country

for a little over a year with our two kids, Mei and Yukon. They

were hers at the time, now they are ours. She left Japan because

of the constraints she experienced over there. She lived on a

commune for awhile then moved to a town nearby. She made a modest

living making futons and sewing. We met at a party in Willits.

I had been living alone for twelve years. Kayo moved in a week

after we met. There was never any doubt. Eda was born then, a

few years later, Anna. We have been together about five years

and I am very grateful for Kayo and my family. I am very happy

to be with them.

In the beginning, we could barely communicate

verbally - which is a really wonderful thing. It is good not to

have to talk to your wife sometimes, but just be there. There

was a lot of space. A lot of quiet and a lot of non-verbal communication.

More than that, there was an understanding - which is really our

vow to each other - that it is all happening right now and not

much else is happening. That is our understanding with each other

and we try to keep it current.

In the beginning, we could barely communicate

verbally - which is a really wonderful thing. It is good not to

have to talk to your wife sometimes, but just be there. There

was a lot of space. A lot of quiet and a lot of non-verbal communication.

More than that, there was an understanding - which is really our

vow to each other - that it is all happening right now and not

much else is happening. That is our understanding with each other

and we try to keep it current.

Kayo comes from one of the most rural

parts of Japan in Shikoku which is the smallest of the main islands.

The village she grew up in calls itself "Tibet-in-Shikoku"

because it is up in the hills and remote. Her parents are farmers

who grow green plums, shitake mushrooms and citrus. They also

have woodland on which they grow cedar. My father-in-law is a

logger who grows and cultivates his trees from scratch.

Kayo brought with her a real feeling

for the land and for nature. Our place here is somewhat reminiscent

of her home. We have a garden right next to the house. In the

wintertime she can make an entire meal out of what is simply at

hand.

We have been sending our kids to Japan

during the summers. They stay with their grandparents and go to

the local elementary school. This school has been attended by

Kayo's family back to the days of her grandmother. It is very

small with only 24 children grades one through six. It is a treat

for them to have Mei and Yukon, who grew up in this village as

part of the school, coming back from America with all their new

experiences to share.

We have a good and sustaining relationship

with the school, with the village and with our family in Japan.

We have a genuine connection over there.

YOU WERE TALKING ABOUT YOUR RESPONSIBILITIES

TO YOUR LAND. NOT TO CUT TREES WITHOUT JUSTIFIED USE, THE IMPACT

OF YOUR LIFE ON A PATCH OF WILDERNESS. WHAT OTHER RESPONSIBILITIES

DO YOU FEEL?

It is analogous to shaping a shakuhachi

bore and dealing with a variety of variables that you try to balance

into a workable form. An ideal type exists in which all of these

variables are balanced to produce a perfect sound. Of course,

nobody can achieve this standard completely. It is the same with

homesteading a piece of land. Basically, you do the best you can

with the resources available. The success of your endeavor is

underlaid by the values and attitude that motivates your energy.

In our case, we live and work on our

land. Our youngest children were born at home. My daughter will

be going to a one-room school in a log cabin built in the 1880s.

It is located at the end of the dirt road on which we live. We

grow as much of our own food as possible, which is never enough.

We are taking an awful lot from the land. That is understood.

The land is supporting us in a very traditional manner. In many

ways, it probably wasn't much different from the ways folks lived

a hundred years ago. The impact you have while juggling those

variables and making the changes on the place itself is what I

am talking about. That is where the responsibility lies.

Working toward self-sufficiency and

independence on a small homestead involves making lots of decisions

which have lasting effects on the land. The rewards in turn are

great. My own home was built largely from salvage as is much of

the alternative energy system that I put together. My home power

system is charged by solar panels and a homemade hydroelectric

generator designed and built by a friend that rivals some of the

best in the world. We pump all of our water with this system which

also runs 95% of my workshop. All of my shakuhachi are made with

alternative energy which is something I feel very good about.

Cutting trees or alter the streams to

accommodate alternative energy projects - yes - those are individual

instances, but the real responsibility is to tune in and get the

information that is emanating from all that surrounds you. Here

we get back to blowing shakuhachi or sitting zazen. It is opening

yourself up to the information at hand, waking up and able to

be there with it so you can get it.

I don't read the newspapers anymore.

I have even gave up the Willits News. There is no information

in these sources that is helping out. My time is better spent

going for a walk down the creek.

What we are talking about, really, is

one's relationship to place and space: the space you occupy and

its impact on the place you inhabit. My family's experience had

a strong effect on me in this regard. My grandparents came to

this country in 1907. They were emigres from persecution in Eastern

Europe. Landing on Ellis Island, they made it across the East

River to Brooklyn where they rented a six-room apartment for thirty

eight years. I grew up in their home and was part of a large extended

family that encompassed an entire neighborhood. My perspective

on this place is interesting. It was at best a slum throughout

the entire era my family lived there. Different ethnic minorities

filtered through as they made their way along the upward mobile

ladder. These groups moved from one neighborhood to the next.

My family was the first to arrive and the last to leave... [laughs].

I suspect it is going to be the same thing here in Willits.

When I was very young I lived in a thriving

ethnic community. It was a good neighborhood. My grandparents

had friends and neighbors who came to America from the same town

in Eastern Europe. My mother never had to worry about me because

someone was always watching.

As I got older the neighborhood changed

drastically. The older folks died and their children moved to

better jobs and safer neighborhoods. My family remained as Black

and Puerto Rican families moved in. At the high school I attended,

white students were in a minority - if you consider Puerto Ricans

non-white and in New York they are. Out of a high school of 3000,

a handful of us went to college. For most of the people in this

neighborhood, English was not the language spoken at home. This

was true of my family as well.

I saw this place change from a vantage

point few people have had the opportunity to see. I caught the

tail end of one era and the beginning of the next which included

gang warfare, hard drugs and an incredible amount of poverty.

I am amazed how hard working most poor people are and how little

credit they are given.

I went back to visit the old neighborhood

after having lived in Willits for a number of years and was taken

totally by surprise. Nobody was living on our block any longer.

The entire side of the street that I had lived on was vacated.

This had happened to square miles of New York City where people

had abandoned entire residential areas that have become uninhabitable.

The whole neighborhood had a bombed out appearance. The house

I lived in was empty. I went up to the apartment and went to my

old room where I removed the door knob. It's now part of my house

in Willits.

Places change and sometimes they change

so radically that people cannot live in them anymore. Many of

the changes some people here would like to see are going to result

in the same scenario. I am talking about a proposed wood burning

power plant to be located in downtown Willits and a freeway by-pass

cutting through our beautiful valley. I am talking about how some

people are working to rezone this community so we can have six

Circle K convenience stores instead of the two that we never really

needed.

Many of the new settlers to this area

have had an experience of place that is similar to my own: seeing

rampant development end up as devastation and decay. That experience

underlies our determination to prevent the future of Mendocino

County and our entire bioregion from following a predictable course.

I think it is time to examine all this

"good old boy" stuff when it is used as the basis for

important community decisions. I am not sure how "good"

these folks are. Our local logging dynasty in Willits realizes

that the forests will not go on forever when they are treated,

essentially, as a source of profit. That is why these people are

trying to get out of the lumber business and divest their assets

into more lucrative forms, like producing and selling electrical

power. In that way they can continue cutting all the trees, hardwoods

included, which is all they seem to know how to do. They are not

producing jobs or well being in this community. They are producing

income and power for themselves in an effort to maintain their

own class position.

I believe that an understanding of social

and economic class is very important to our understanding of how

thing work. People's lives are affected adversely on every level

of society. There are structural issues at the core of these personal

problems we encounter. Class is one perspective that is incredibly

glossed over in this country.

SO IT'S NOT JUST AN EMERGING CULTURE

HERE, IS IT? IT'S ALSO AN EMERGING CLASS.

Very much so. It is extremely important

to distinguish who we are and what we are doing from that which

is occurring in the main drift of society. I avoid using the terms

"we" and "us" when talking about the United

States of America. I`d rather talk about what I am involved in

as an individual or in cooperation with my friends. My understanding

of class makes me feel closer to ordinary people throughout the

world than to my own government and its corporate owners.

As a class - both local and global -

or as individuals sincerely concerned with the fate of the earth,

we need to take into account all of the developments that are

occurring around us. We need to inform ourselves and act from

a conscious state which means eliminating some illusions so we

can establish a foundation and move toward a positive vision of

the future. One that can support us for a long, long time right

here on this planet.

I agree with Gary Snyder. We have to

start thinking a thousand years ahead. We must begin doing that

if we are going to remain in our place. Otherwise, it is going

to become like the old neighborhood in Brooklyn.

WHAT DO YOU THINK IS THE MEANING OF

THAT ORIGINAL LEGEND WHERE EVERYTHING FUKE ENCOUNTERED HE HIT?

I'm not sure. That is what I am trying

to find out. In some way, when I blow shakuhachi I am doing that

with each note.

This interview first appeared in the NEW SETTLER

INTERVIEW, an alternative bioregional magazine covering the emerging rural culture

of northwest California and sourthern Oregon. It is written in the words of

those people who are creating that culture. For more information and subscriptions,

contact Beth Bosk, New Settler Interview, P.O. Box 702 Mendocino CA. 95460.

There is something more than tradition, culture

and rituals passed down over a long period of time that is going

to help us out in the end. My particular interest is in the stuff

that underlies or cuts through culture, that connects us all as

a species, as human beings.

There is something more than tradition, culture

and rituals passed down over a long period of time that is going

to help us out in the end. My particular interest is in the stuff

that underlies or cuts through culture, that connects us all as

a species, as human beings. I am still very much a western man. But more

than assuming any given posture or presenting certain characterizations,

my interest is in learning. If you keep at something long enough,

you come to the limit of certain parameters. At that juncture

you can either stay where you are or open yourself up to other

forms and processes.

I am still very much a western man. But more

than assuming any given posture or presenting certain characterizations,

my interest is in learning. If you keep at something long enough,

you come to the limit of certain parameters. At that juncture

you can either stay where you are or open yourself up to other

forms and processes. I spent a good deal of time making mediocre

flutes. They were out of tune and funky. But they blew the basic

stuff and everyone I met loved them. That kept me going. I didn't

have much of a notion to make "great" instruments. I

didn't know much about what I was doing.

I spent a good deal of time making mediocre

flutes. They were out of tune and funky. But they blew the basic

stuff and everyone I met loved them. That kept me going. I didn't

have much of a notion to make "great" instruments. I

didn't know much about what I was doing. In the beginning, we could barely communicate

verbally - which is a really wonderful thing. It is good not to

have to talk to your wife sometimes, but just be there. There

was a lot of space. A lot of quiet and a lot of non-verbal communication.

More than that, there was an understanding - which is really our

vow to each other - that it is all happening right now and not

much else is happening. That is our understanding with each other

and we try to keep it current.

In the beginning, we could barely communicate

verbally - which is a really wonderful thing. It is good not to

have to talk to your wife sometimes, but just be there. There

was a lot of space. A lot of quiet and a lot of non-verbal communication.

More than that, there was an understanding - which is really our

vow to each other - that it is all happening right now and not

much else is happening. That is our understanding with each other

and we try to keep it current.